Authors note: due to undertaking a new work contract where I would have a conflict of interest in writing most news or analysis for this blog, I regret to inform folks that after a fun short starting run, we may be unable to deliver content in the same way going forward. To that end, content on this blog authored by myself will be going on an indefinite hiatus, as is our “every Wednesday and Friday” commitment. Thank you to all our early supporters here, it has been nice to have an audience,and we hope to continue to find ways to deliver you content. Please enjoy this last blog for the immediate future, and feel free to reach out to us through our contact form.

The University of Toronto Students’ Union has accomplished something. After years of having a unicameral Board structure, at a recent AGM, it voted to adopt a 12-person Board and segment its more representational functions into a Council. In honour of this, I wanted to take a look into the

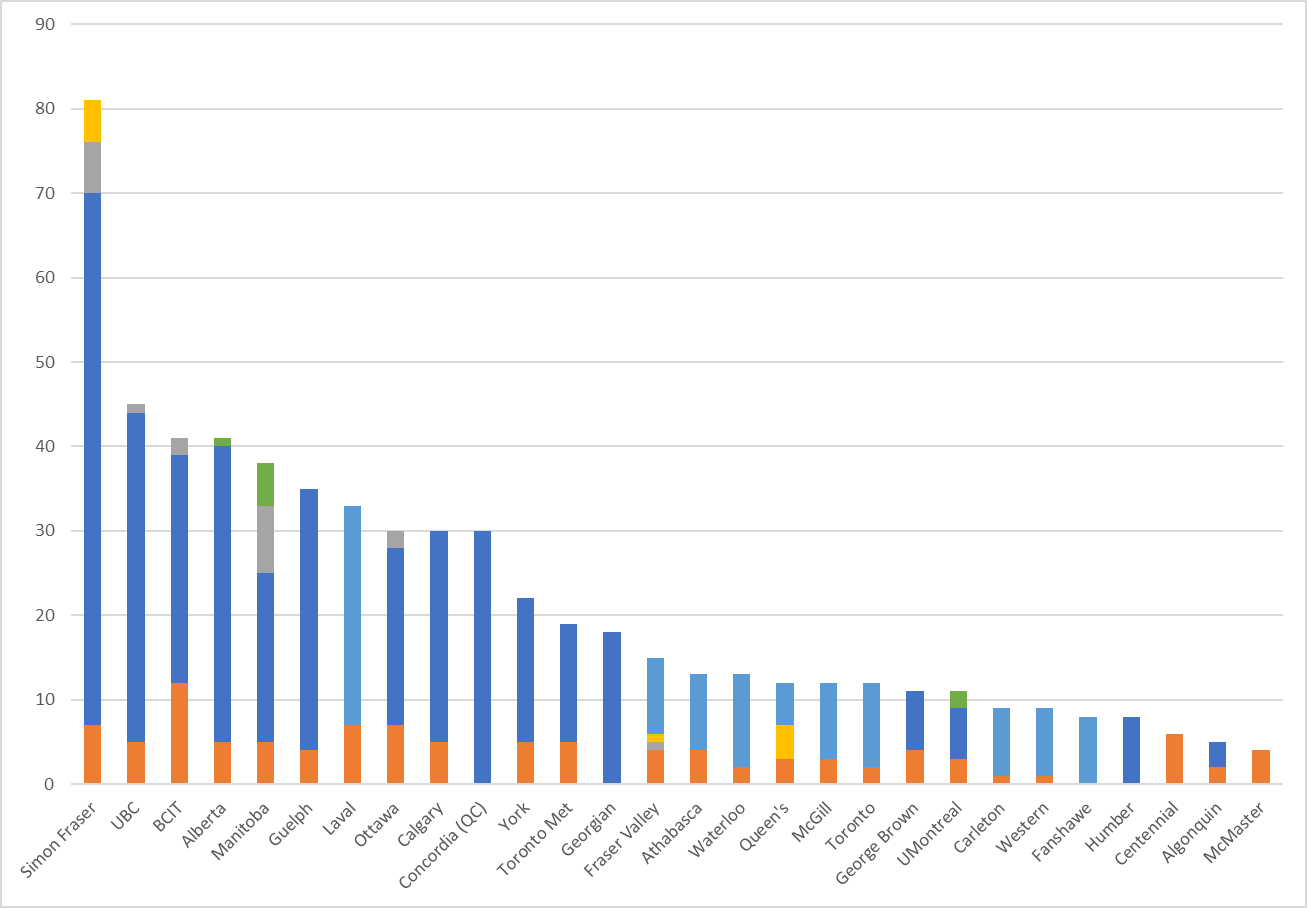

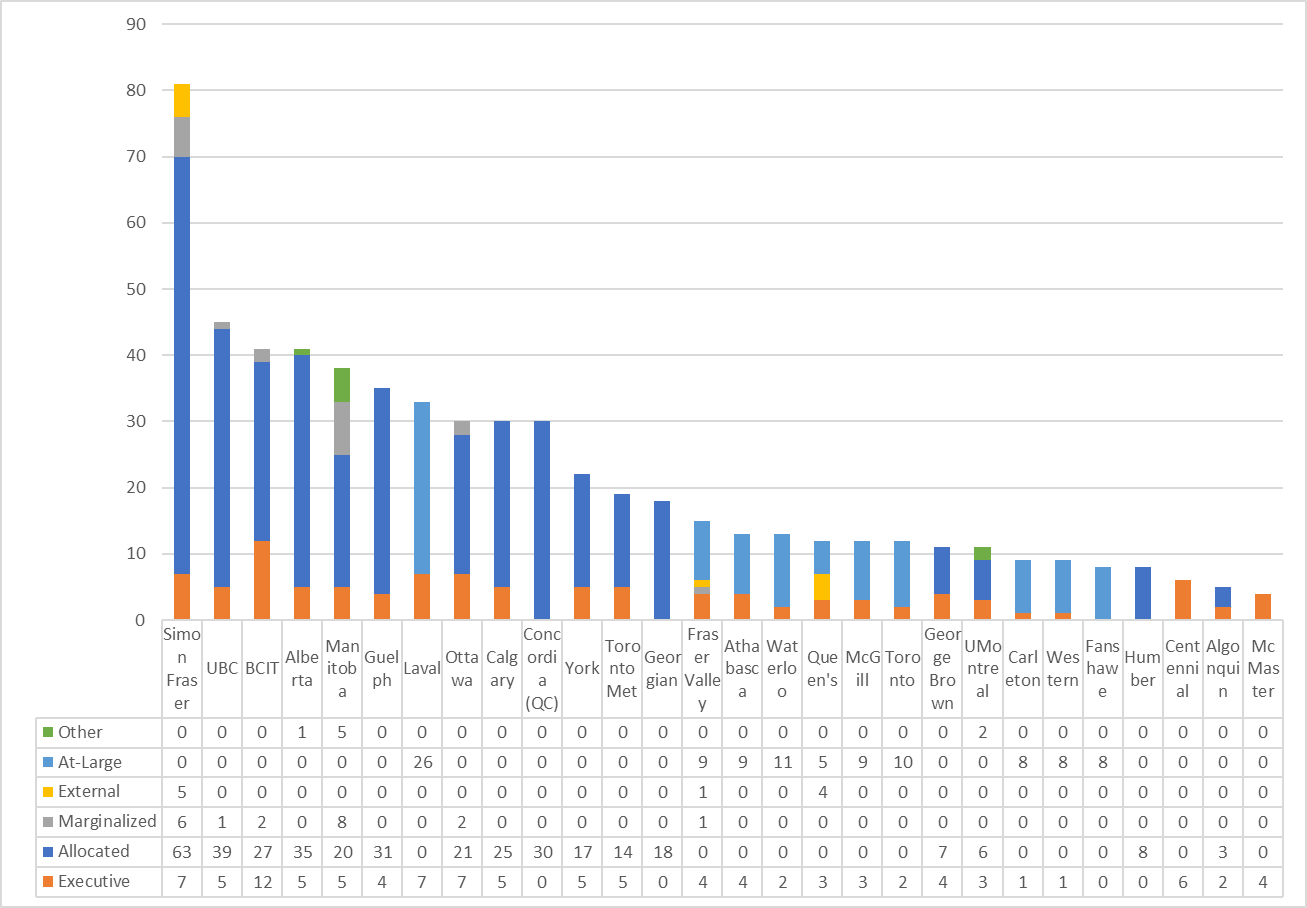

Today’s figure is 2025%. That’s the level of difference between the size of the Board at McMaster’s Student Union (4) and the size of the Simon Fraser Student Society (81).

Today we’re looking at the size of Boards of Directors and their composition, specifically in Super Large Unions. Today, we’re looking at size and who gets the spots.

For the purposes of this analysis, we’re looking at voting seats, and dividing seats into 1) Executive seats 2) Seats by faculty, location, or college 3) External Directors 4) Seats for marginalized folks and 5) Seats elected at-large.

We also look at whether these “Boards” have complementary Councils. This is relevant since one benefit of larger Boards might be that when you don’t have a Council, a bigger Board gives a wider span of student representation. We use the terminology here of “Board” for any organization that is a functional legal Board of Directors, and “Council” as an internal representative organ that doesn’t have fiduciary duty. The names of both can vary.

We’ll give you the graphs (one with a data table), then tell you what you’re looking at and what’s important below.

Bicameral institutions are: Laval, Queen’s, McGill, Toronto, Montreal, Carleton, Western and McMaster.

Observations

Size and Functions

First, there is a lot of range. This is true even between unicameral (Board-only) institutions. A hypothesis here is that there is a spectrum of Board-only organizations, with organizations like Simon Fraser Student Society (SFSS) using their Board as a primary mechanism for student input, discharging its more traditional Board duties (like finance, strategic visioning and HR) through committees and executive, UBC Alma Mater Society does this through having a non-fiduciary Advisory Board who has functions similar to what you might see from a Board elsewhere. This necessitates a larger number of students from prescribed academic backgrounds to get a wider cross-section of students.

A smaller Board like Algonquin is more likely to only do traditional Board duties, outsourcing the student input mechanism to other tools, like their advisory class rep system, which has no powers under its bylaws.

We can see potential supporting evidence of this hypothesis through seeing the increased prevalence of at-large election of directors in smaller boards, while larger boards tend to have more “allocated” seats.

Among the bicameral institutions, Laval stands out as an exception as being large, but the rest of those using a bicameral structure are small, implying that the core work of a Board can be done by relatively few when the function of debating political positions is passed off to a secondary body.

Regional Variations are Common

A second observation is that there are many regional variations. The five largest Boards occur west of Ontario. Of the five smallest, all are in Ontario. Four of them are colleges.

There are some other patterns below the surface too, such as structural factors like the Alberta Post-Secondary Learning Act, whose language under Section 95(4) structures the unicameral Board as “the council of a students association is the official channel of communication between the students of a public post-secondary institution“. These and other provisions in the Act seem to be behind the push towards a unicameral structure, indirectly leading to larger Board sizes.

A second trend worth identifying here is the BC focus on inclusion of seats specifically reserved for marginalized groups. Without assessing merit of these seats or the effectiveness of achieving their goals, it is interesting to see all BC schools include at least one seat, and only two others in other provinces.

External Directors are Rare

While for-profits or larger non-profits may often use boards with a wide range of external directors, often those who are themselves executives in successful businesses, or prolific members of society.

This is rare in the student association world. Simon Fraser includes five directors that represent student organizations outside of the association, like a residence council. So they only narrowly meet the definition. The University of the Fraser Valley has a Board Chair who has a vote only in the case of a tie.

The only studied organization with regular voting representation of external directors is the Queen’s Alma Mater Society.

Why might this be?

One element that usually permits the cross-pollination of businesspeople or charity executives is that Boards are usually hands off enough that time and expertise required to participate is low. While these external directors might have general skills in strategic foresight or finance, they don’t need to know the specifics.

This might be less viable in student associations. If you adopt the premise that association boards are often more hands on than other Boards to retain the value of student-based priority setting, this might explain why organizations have remained with the more student directors.

Executive are Common

There is a strain of thought that says “begone executive”, but if it exists in Canada’s large institutions, it is rare, only occurring in four organizations.

The theoretical motivation here likely comes from traditional governance principles about division of labour: the management (executive) is supposed to be controlled by the board, not exert their opinions on the board through voting on it. This would allow the board to focus deeply on strategic direction, and the executive on making the organization work smoothly towards those directions.

But unlike traditional governance situations, the “for-students-by-students” ethos of associations usually leads to student executives and student-based boards. This leads to retention of executive on boards for at least three reasons,

1) student executive are elected and therefore presumed to have some role to play on strategic direction

2) student executive being fully engaged on a board leads tothem serving as a bridge to inform a relatively amateur board about organizational inner workings; and,

3) to serve as a voting bloc to represent internal organizational interests to counter possible over-reactionary tendencies in relatively inexperienced directors.

For most organizations, the compromise between these two strains of thought seems to be ensuring that executive sit on boards but represent only a minority of seats.

There are two more exceptions, which have only executive, the McMaster Students Union and Centennial’s CCSAI. CCSAI is an edge case, with executive being styled as VP (Satellite Campus), but they may serve more as allocated seats depending on interpretation.

The McMaster Students Union manages the “outside perspective” issue through having an “executive board”, that serves basically as a normal board of directors, with the legal Board only exercising its power when meeting in the presence of that wider body.

Oddities and Notes

A few odds and ends also occur to me.

A few organizations have auto-adjusting formulae for their council size, such as the University of Calgary and the University of British Columbia’s boards.

Very notable to me is the Simon Fraser Student Society, and some others allocate seats to academic units without necessarily having regard for the number of students in those units. This ensures wide coverage of students, but also inhibits strong proportionality of representation.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that small colleges may tend to have “allocated seats” instead of “at-large seats” unlike other small associations. This is often explained by having representation based on different campuses.

And with that I guess, we’re #OFF, in a bit of a different way this time.

Leave a comment